About The Campaign

‘A Place Like Home’ was created with the purpose of providing information regarding unaccompanied minors in Europe and to respond, raise awareness, and provide an overview of the situation of refugee and migrant children in terms of integration including shelter and accomodation, education needs, and family reunification.

According to UNICEF, despite drastic measures to stop irregular migration, including pushback at borders and constraints on rescue operations, the influx is expected to remain high.

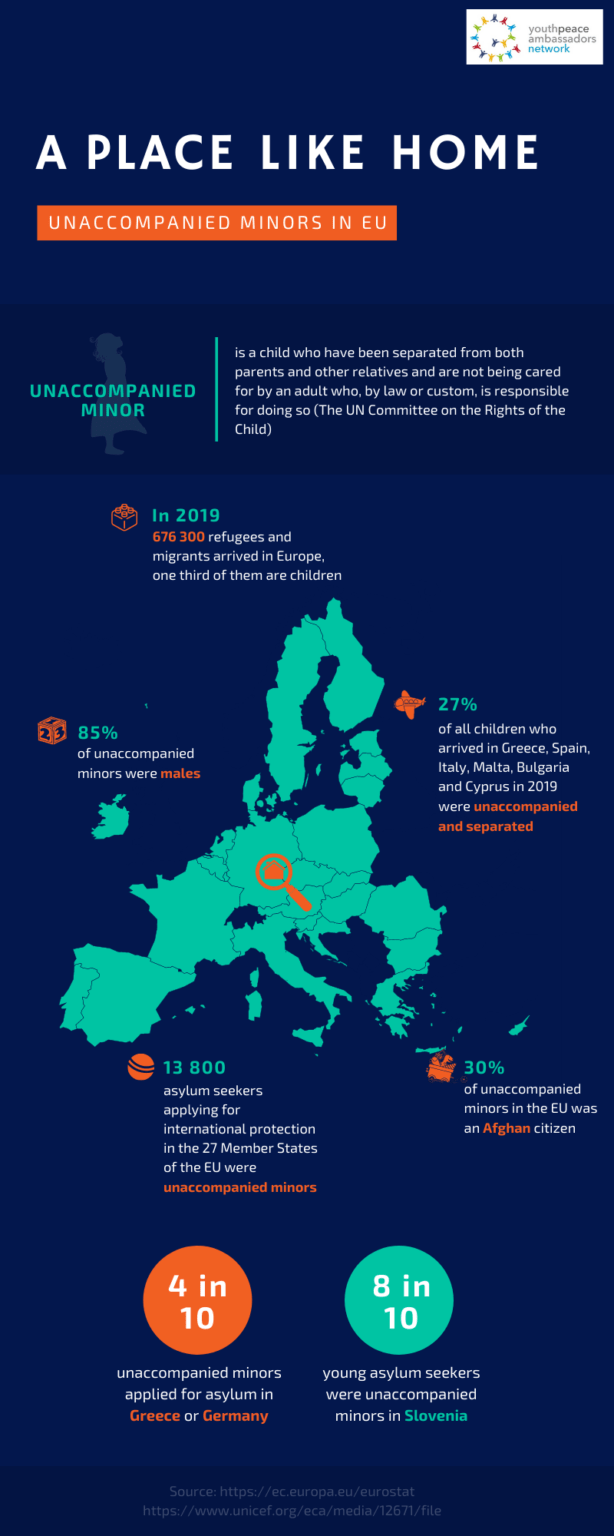

In 2019, 676,300 refugees and migrants arrived in Europe, around 30 % of them are children. With the recent spike in the number of arrivals on the Eastern Mediterranean route, the situations in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in the Greek Islands remain challenging, with over-crowding, unsafe accommodations and limited access to basic services.

Furthermore, girls and boys traveling alone – are the most vulnerable to abuse and exploitation, including gender – based violence.

Why do Unaccompanied minors come to the EU?

- To escape from wars & conflicts, poverty, natural disasters, discrimination, and persecution. These can often lead to serious harm or death and necessitate minors seeking international protection.

- These conditions lead to minors seeking a better life. Whether economic, aspirational, or simply to live in a safe and accepting environment.

- Many of these minors are fleeing the reality of human trafficking. This can be sexual exploitation, forced labor, etc…

Where do unaccompanied minors live while in the EU?

The answer is complex because there is not one type of accommodation that UAMs stay in and they are often moving between accommodations based on the member state’s capacities in staff and premises, laws and regulations, and practice.

The language used can also be confusing because terms such as ‘group home’, ‘youth welfare institutions’, ‘child protection residential units’ and ‘specialised residential homes’ are used to describe where UAMs are accommodated.

Some member states offer specialised facilities for UAMs, while others will place them in mixed dormitories with unrelated adults. UAMs staying in facilities with adult asylum seekers have complained of sleep deprivation due to loud noise, gambling and alcohol consumption at night by adults in their rooms, or of being forced to run errands like cleaning, laundering and shopping for adults.

The quality of accommodation is extremely varied across the EU. At the very basic level UAMs will receive accommodation, meals and healthcare, yet in some cases accommodations are overcrowded and unsanitary. Some member states do better and offer language classes, socio-educational activities, and psychosocial support.

While the EU relocation plan has been welcomed by children’s rights groups, it leaves more than 43,000 refugee and migrant children stranded in Greece, according to UNICEF estimates from last December. Close to 5,000 of them are unaccompanied. On the islands, there are currently some 10,000 migrant and refugee children, some 12% of whom are unaccompanied. That’s according to the most recent UNHCR figures.

Many of these children are locked down in dangerously overcrowded and unsanitary camps on the Aegean islands, the biggest of which is Moria on Lesbos.

Although the Greek government has moved more than 14,000 migrants from Lesbos to facilities on the Greek mainland since January to try to relieve the overcrowding, some 15,000 people remain in Moria. The capacity of the camp is around 2,800 people.

The children there, already exposed to risks to their mental health according to experts, are suffering under added strain in an atmosphere of heightened fear and violence.

“I have not seen my family since I was 7 years old. My brother found me through the Red Cross, but he couldn’t find the rest of my family.

UAMs & Education

Access to education is incredibly important for UAMs’ development, social inclusion and integration into host communities. One of the first barriers when it comes to accessing the education system is language. Many UAMs first spend time learning the local language before they are able to integrate into the education system. Nonetheless, there exists a debate whether UAMs should directly be integrated into the mainstream education system or whether they should begin with a specialised education that takes their educational and cultural background as well as mental health into account.

Significantly, UAMs want to go to school. 38% of children interviewed in a UNICEF-REACH survey in Italy 2017 named education as one of their objectives for coming to Europe.

Unfortunately, the path to education can be very difficult as some host communities have insufficient interest and places to support UAMs, refugee and migrant children. Another large issue concerns UAMs 16 or older who are soon turning 18 and are then cut off from national child protection support. This leaves many teenage aged UAMs frustrated and with limited opportunities as well as putting them at higher risk of dropping out of school.

Return of Unaccompanied Minors

“Durable solutions are crucial to establish normality and stability for all children in the long term. The identification of durable solutions should look at all options… It is essential that a thorough best interests determination be carried out in all cases… Member States should establish procedures and processes to help identify durable solutions on an individual basis, and clearly set out the roles and duties of those involved in the assessment, in order to avoid that children are left for prolonged periods of time in limbo as regards their legal status.”